Excerpt

Chapter 1: A River That Couldn’t Be Tamed

The Colorado River doesn’t look like anything special when you first see it—just a strip of muddy water winding through canyons and deserts. But don’t let that fool you. This river is tough, wild, and incredibly powerful. It’s carved through solid rock, formed one of the biggest canyons in the world, and caused more than a few headaches for people trying to live near it.

It begins in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, where snow from high peaks melts into chilly streams. These small streams twist and turn, then come together like fingers forming a fist. That’s where the Colorado River begins. From there, it travels through seven U.S. states and even reaches into Mexico. It stretches for about 1,450 miles, which is longer than a trip from New York City to Dallas, Texas. And along the way, it never really behaves.

The land the river travels through is dry—really dry. Most of it is desert, and the rain doesn’t fall very often. That makes the river super important. It brings water to places where plants and animals would never survive without it. Cities, farms, and towns all count on the Colorado River, even if they’re hundreds of miles away. You can think of it as a moving lifeline, twisting through cliffs and dust, making life possible where it otherwise wouldn’t be.

But here’s the problem: the river is unpredictable. Some years, it rushes with melted snow and crashes through valleys, strong and fast. Other years, it’s slow and skinny, like it’s run out of energy. And when it floods, it doesn’t just spill a little—it can burst over its banks and wash away anything in its path. People who tried to build homes or farms near it had to always be on alert, wondering if the river would turn against them.

Before giant dams were built, the Colorado River did whatever it wanted. Farmers would dig ditches to bring water to their crops, but those ditches might dry up by summer or get washed away by surprise floods. Entire towns near the river had to rebuild again and again after storms or river swells. And when the river dried up during hot months, it left behind cracked dirt and thirsty animals.

People couldn’t just tell the river to calm down. It didn’t listen. The only way to get control was to build something big—something stronger than floods, tougher than droughts, and smart enough to help everyone who needed water. But before that happened, the river had centuries of freedom. It carved the Grand Canyon. It fed millions of fish and birds. It moved sand, trees, and even boulders. It didn’t just shape the land—it ruled it.

When explorers from Europe came across it hundreds of years ago, they were shocked. They called it “El Rio Colorado” because of its reddish-brown water. That color came from all the silt—tiny pieces of rock and clay—it carried along. Over time, the name stuck. Even today, after all the changes people have made, it still flows with that same rusty color in many places.

The river doesn’t stay one size. At the start, it’s narrow and fast, dashing downhill like it’s late for something. As it travels farther, it widens, slows down, and twists through deep canyons and wide valleys. In some places, you could throw a rock across it. In others, it stretches so far you’d need a boat to get from one side to the other.

Even though the Colorado River runs through some of the hottest, driest places in North America, it’s packed with life. Frogs sing from its banks. Beavers chew down trees near its edge. Birds rest in the reeds that grow where water meets sand. It’s not just a river—it’s a home.

And here’s something that surprises a lot of people: the river doesn’t always reach the sea anymore. It used to end in the Gulf of California, sending its last drops into the ocean. But these days, so much water is taken out for farming and cities that sometimes the river dries up before it gets there. That’s like a runner who gets tired right before the finish line.

Why people needed to control the river

People used to think they could live near the Colorado River without too much trouble. Build a farm, dig a few ditches, grow some crops—easy, right? But the river had other plans. Some days it acted like a friend, bringing water just when it was needed. Other times, it turned wild and smashed through everything like it was in a bad mood. And then there were stretches where it seemed to vanish into thin air, barely a trickle left. That made it nearly impossible to depend on.

This wasn’t just annoying. It was dangerous.

Let’s say you were a farmer in the early 1900s trying to grow lettuce or cotton in the desert. You might spend months planting and watering and hoping for a good harvest. Then, right before your crops were ready, the river might flood and sweep away everything—plants, tools, fences, even your house. Or, the opposite might happen. The river would dry up, and all your crops would wither in the heat. No food. No money. Just cracked ground and broken dreams.

It wasn’t just farms that suffered. Entire towns depended on the river for water. That meant drinking water, bath water, water for washing clothes and keeping animals alive. When the river dried up or got blocked by fallen trees or landslides, people were left with nothing but dust. And when it raged, it didn’t just overflow its banks—it could move heavy rocks, destroy roads, and cut off towns from the rest of the world.

This kind of chaos couldn’t go on forever. More and more people were moving to the Southwest, building homes and starting businesses. Cities like Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Las Vegas were beginning to grow. But those cities didn’t have their own rivers. They needed help, and the Colorado seemed like the answer—if only someone could figure out how to stop it from misbehaving.

The trick was finding a way to get just the right amount of water—enough for everyone, but not so much it would drown everything. That meant building something that could slow the river down when it was moving too fast, store water when it was moving too slow, and send it where it was needed. That was no small task.

There was another problem, too: the river crossed through several different states. That meant Arizona, Nevada, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Wyoming, and California all wanted a share. They weren’t always very good at sharing. Each state wanted water for its own cities, farms, and people. But the river wasn’t getting any bigger, and fights started breaking out over who deserved what.

To stop all this arguing—and to avoid running out of water entirely—leaders from these states started talking about a plan. If they could figure out how to divide the river’s water fairly and store it safely, everyone could benefit. But to do that, they needed a massive structure. Something that could hold back millions of gallons of water. Something that could release water slowly, on purpose, instead of all at once by accident. Something that could even turn water into power for homes, lights, and factories.

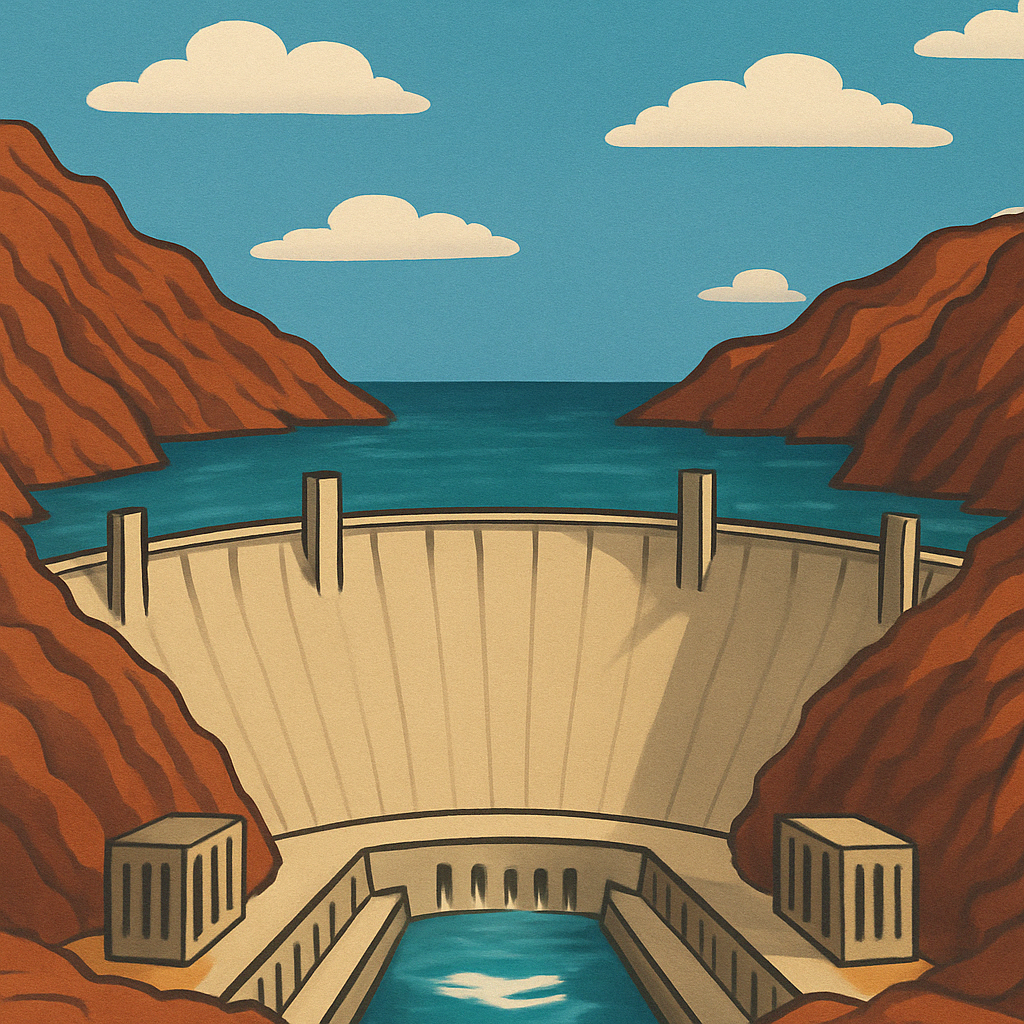

They needed a dam. A huge one.

This wasn’t just about water. It was about survival. It was about helping people live in a place where the sun beat down like a hammer and the rain barely showed up. Controlling the Colorado River wasn’t a “nice-to-have.” It was the only way to make the desert livable for more than a handful of tough settlers. And people were ready to try—no matter how hard the job would be.

Floods had already shown what happened when there was no control. One of the worst disasters happened in California’s Imperial Valley in 1905. Engineers had built a canal to send river water to the valley’s farmland. But during a flood, the river smashed through the canal and carved a brand-new path into the valley. It created a giant lake where there wasn’t supposed to be one—called the Salton Sea—and it took years and millions of dollars to stop the damage. It was like the river had shrugged and decided, “I’ll just go this way now.”

That event scared a lot of people. If the river could do that once, what would stop it from doing it again?

To avoid another disaster, engineers began to study the river more carefully. They measured how high it got during floods. They tracked where the biggest bends and turns were. They studied the land around it to find a spot strong enough to hold the weight of a wall taller than a skyscraper. After years of searching, they found the perfect location: Black Canyon, right between Nevada and Arizona.

Still, not everyone was convinced. Some people thought trying to control a river this powerful was foolish. Others worried it would cost too much or take too long. But the people who believed in the project weren’t just thinking about today—they were thinking about the future. If they could figure out how to manage the river, they could bring water to dry places, prevent deadly floods, and even generate electricity.

The Southwest was growing fast. More people meant more need for everything: food, homes, water, power. And the Colorado River was the only thing nearby that could supply all of that—if someone could just take charge.

Taming the river wouldn’t be easy. It would take thousands of workers, a brand-new city just to house them, and engineering ideas no one had tried before. But the reason behind it all was simple: people needed water. Not when the river felt like giving it, but every single day. On hot days, on dry days, even during long, punishing droughts. They needed protection from the floods and a promise that the river wouldn’t destroy everything they’d worked for.

They needed the Colorado River to stop being wild—and start being useful.

The Colorado River doesn’t look like anything special when you first see it—just a strip of muddy water winding through canyons and deserts. But don’t let that fool you. This river is tough, wild, and incredibly powerful. It’s carved through solid rock, formed one of the biggest canyons in the world, and caused more than a few headaches for people trying to live near it.

It begins in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, where snow from high peaks melts into chilly streams. These small streams twist and turn, then come together like fingers forming a fist. That’s where the Colorado River begins. From there, it travels through seven U.S. states and even reaches into Mexico. It stretches for about 1,450 miles, which is longer than a trip from New York City to Dallas, Texas. And along the way, it never really behaves.

The land the river travels through is dry—really dry. Most of it is desert, and the rain doesn’t fall very often. That makes the river super important. It brings water to places where plants and animals would never survive without it. Cities, farms, and towns all count on the Colorado River, even if they’re hundreds of miles away. You can think of it as a moving lifeline, twisting through cliffs and dust, making life possible where it otherwise wouldn’t be.

But here’s the problem: the river is unpredictable. Some years, it rushes with melted snow and crashes through valleys, strong and fast. Other years, it’s slow and skinny, like it’s run out of energy. And when it floods, it doesn’t just spill a little—it can burst over its banks and wash away anything in its path. People who tried to build homes or farms near it had to always be on alert, wondering if the river would turn against them.

Before giant dams were built, the Colorado River did whatever it wanted. Farmers would dig ditches to bring water to their crops, but those ditches might dry up by summer or get washed away by surprise floods. Entire towns near the river had to rebuild again and again after storms or river swells. And when the river dried up during hot months, it left behind cracked dirt and thirsty animals.

People couldn’t just tell the river to calm down. It didn’t listen. The only way to get control was to build something big—something stronger than floods, tougher than droughts, and smart enough to help everyone who needed water. But before that happened, the river had centuries of freedom. It carved the Grand Canyon. It fed millions of fish and birds. It moved sand, trees, and even boulders. It didn’t just shape the land—it ruled it.

When explorers from Europe came across it hundreds of years ago, they were shocked. They called it “El Rio Colorado” because of its reddish-brown water. That color came from all the silt—tiny pieces of rock and clay—it carried along. Over time, the name stuck. Even today, after all the changes people have made, it still flows with that same rusty color in many places.

The river doesn’t stay one size. At the start, it’s narrow and fast, dashing downhill like it’s late for something. As it travels farther, it widens, slows down, and twists through deep canyons and wide valleys. In some places, you could throw a rock across it. In others, it stretches so far you’d need a boat to get from one side to the other.

Even though the Colorado River runs through some of the hottest, driest places in North America, it’s packed with life. Frogs sing from its banks. Beavers chew down trees near its edge. Birds rest in the reeds that grow where water meets sand. It’s not just a river—it’s a home.

And here’s something that surprises a lot of people: the river doesn’t always reach the sea anymore. It used to end in the Gulf of California, sending its last drops into the ocean. But these days, so much water is taken out for farming and cities that sometimes the river dries up before it gets there. That’s like a runner who gets tired right before the finish line.

Why people needed to control the river

People used to think they could live near the Colorado River without too much trouble. Build a farm, dig a few ditches, grow some crops—easy, right? But the river had other plans. Some days it acted like a friend, bringing water just when it was needed. Other times, it turned wild and smashed through everything like it was in a bad mood. And then there were stretches where it seemed to vanish into thin air, barely a trickle left. That made it nearly impossible to depend on.

This wasn’t just annoying. It was dangerous.

Let’s say you were a farmer in the early 1900s trying to grow lettuce or cotton in the desert. You might spend months planting and watering and hoping for a good harvest. Then, right before your crops were ready, the river might flood and sweep away everything—plants, tools, fences, even your house. Or, the opposite might happen. The river would dry up, and all your crops would wither in the heat. No food. No money. Just cracked ground and broken dreams.

It wasn’t just farms that suffered. Entire towns depended on the river for water. That meant drinking water, bath water, water for washing clothes and keeping animals alive. When the river dried up or got blocked by fallen trees or landslides, people were left with nothing but dust. And when it raged, it didn’t just overflow its banks—it could move heavy rocks, destroy roads, and cut off towns from the rest of the world.

This kind of chaos couldn’t go on forever. More and more people were moving to the Southwest, building homes and starting businesses. Cities like Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Las Vegas were beginning to grow. But those cities didn’t have their own rivers. They needed help, and the Colorado seemed like the answer—if only someone could figure out how to stop it from misbehaving.

The trick was finding a way to get just the right amount of water—enough for everyone, but not so much it would drown everything. That meant building something that could slow the river down when it was moving too fast, store water when it was moving too slow, and send it where it was needed. That was no small task.

There was another problem, too: the river crossed through several different states. That meant Arizona, Nevada, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Wyoming, and California all wanted a share. They weren’t always very good at sharing. Each state wanted water for its own cities, farms, and people. But the river wasn’t getting any bigger, and fights started breaking out over who deserved what.

To stop all this arguing—and to avoid running out of water entirely—leaders from these states started talking about a plan. If they could figure out how to divide the river’s water fairly and store it safely, everyone could benefit. But to do that, they needed a massive structure. Something that could hold back millions of gallons of water. Something that could release water slowly, on purpose, instead of all at once by accident. Something that could even turn water into power for homes, lights, and factories.

They needed a dam. A huge one.

This wasn’t just about water. It was about survival. It was about helping people live in a place where the sun beat down like a hammer and the rain barely showed up. Controlling the Colorado River wasn’t a “nice-to-have.” It was the only way to make the desert livable for more than a handful of tough settlers. And people were ready to try—no matter how hard the job would be.

Floods had already shown what happened when there was no control. One of the worst disasters happened in California’s Imperial Valley in 1905. Engineers had built a canal to send river water to the valley’s farmland. But during a flood, the river smashed through the canal and carved a brand-new path into the valley. It created a giant lake where there wasn’t supposed to be one—called the Salton Sea—and it took years and millions of dollars to stop the damage. It was like the river had shrugged and decided, “I’ll just go this way now.”

That event scared a lot of people. If the river could do that once, what would stop it from doing it again?

To avoid another disaster, engineers began to study the river more carefully. They measured how high it got during floods. They tracked where the biggest bends and turns were. They studied the land around it to find a spot strong enough to hold the weight of a wall taller than a skyscraper. After years of searching, they found the perfect location: Black Canyon, right between Nevada and Arizona.

Still, not everyone was convinced. Some people thought trying to control a river this powerful was foolish. Others worried it would cost too much or take too long. But the people who believed in the project weren’t just thinking about today—they were thinking about the future. If they could figure out how to manage the river, they could bring water to dry places, prevent deadly floods, and even generate electricity.

The Southwest was growing fast. More people meant more need for everything: food, homes, water, power. And the Colorado River was the only thing nearby that could supply all of that—if someone could just take charge.

Taming the river wouldn’t be easy. It would take thousands of workers, a brand-new city just to house them, and engineering ideas no one had tried before. But the reason behind it all was simple: people needed water. Not when the river felt like giving it, but every single day. On hot days, on dry days, even during long, punishing droughts. They needed protection from the floods and a promise that the river wouldn’t destroy everything they’d worked for.

They needed the Colorado River to stop being wild—and start being useful.